"Always be prepared to give a defense to everyone who

asks you to explain the hope you have."

(I Peter 3: 15)

In the last chapter we focused on the importance of pathos in logos (speech or discourse). There must be passion in the speaker and the message must affect the emotions. We saw pathos in the speech of Christ and of the apostle Paul. Let us enlarge upon Paul's pathos, especially since he had more to say about logos and Christian speech, in answer to the Sophists and Rhetoricians, than any other new testament writer.

Paul vs. Sophists

"You know, brothers and sisters, that our visit to you was not without results. We had previously suffered and been treated outrageously in Philippi, as you know, but with the help of our God we dared to tell you his gospel in the face of strong opposition. For the appeal we make does not spring from error or impure motives, nor are we trying to trick you. On the contrary, we speak as those approved by God to be entrusted with the gospel. We are not trying to please people but God, who tests our hearts. You know we never used flattery, nor did we put on a mask to cover up greed—God is our witness. We were not looking for praise from people, not from you or anyone else, even though as apostles of Christ we could have asserted our authority. Instead, we were like young children among you." (I Thess. 2: 1-7 NIV)

In the above words we can see the manner of speaking of the apostle contrasted with that of the Sophists. The Sophist in his discoursing makes his "appeal" ("exhortation" kjv) "from error or impure motives," but the apostle makes his appeal from the truth, from the purest of motives, from good ethos. Sophist discourse is intended to "trick" or fool people, much like marketers and advertisers do today, but the discourse of the apostle was intentionally frank and honest with his hearers.

Sophist discourse and speech was designed to "tickle the ears" of an audience, to "please people" so that the speaker might be praised. Sophists looked for popularity and fame, for power and influence. Such was not the case with the apostle. The Sophists were in it for the money and not out of any love for the truth nor for the real benefit of people. The speaking of the Sophist was designed to improve the well being of the Sophist and not to improve the well being of the people whom they seek to fool.

Notice how Paul speaks of making "appeal" to hearers of his discoursing, to his homilies. Notice also his reasoning, his logical argument, his offering proof and evidence, his logos. Notice also how he appeals to the people to consider his ethos, his character and life as proof of his assertions. Notice also how he clearly speaks with sincerity, with emotion, and how he appeals not to the intellect alone but also to the feelings and emotions of those he addressed. He says of himself and his companions - "we were as small children among you," meek and humble, not proud and arrogant, not authoritarian.

You can see the shifting moods of the apostle in each sentence he writes. When he speaks of having to discourse in the face of "much opposition" he no doubt spoke with emotion. When he says things in defense of the attacks upon him by the Sophists he no doubt feels a different mood and calls upon his hearers to feel what he is feeling in the remarks he makes. Now, let us look at another example of Paul's preaching essentials.

Paul vs. Tertullus

Their Debate

"And after five days Ananias the high priest descended with the elders, and with a certain orator (Greek "rhetor" lawyer, advocate, or forensic discourse or debate) named Tertullus, who informed the governor against Paul. And when he was called forth, Tertullus began to accuse (kategoreo, a legal term for what prosecutors do) him, saying, Seeing that by thee we enjoy great quietness, and that very worthy deeds are done unto this nation by thy providence, We accept it always, and in all places, most noble Felix, with all thankfulness. Notwithstanding, that I be not further tedious unto thee, I pray thee that thou wouldest hear us of thy clemency a few words.

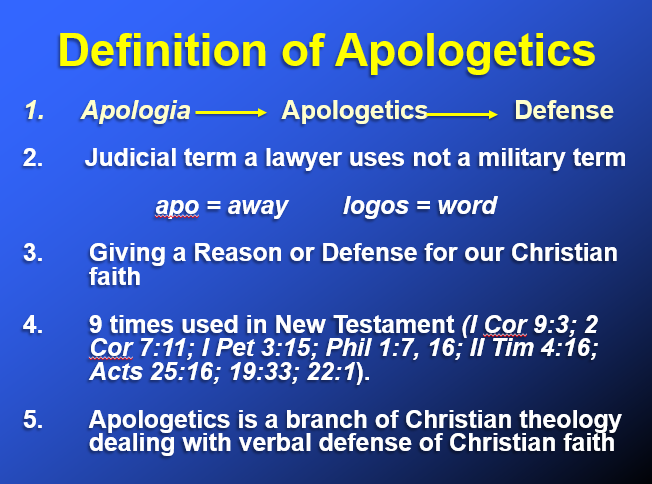

Notice the courtroom setting and drama. Notice the elites who are present, the wise and powerful, and the Sophist flattery which begins the oration of Tertullus. He begins by heaping lofty praise upon the governor (Felix), the one who is to try the case. He uses terms applicable to a deity, speaking of Felix as the source of great social peace and well being of all the people, and of his benevolent "providence" and numerous "worthy deeds." He speaks of Felix as "most noble." "Noble" is from "kratistos" and means "most illustrious," or "most excellent," and was the word used when addressing persons of high rank or office. Notice too the lengthy introduction and the use of pathos by Tertullus and how his speech is mostly without any logos or logical argument. Also notice how Paul's debate with Tertullus and the presentation of his case to Felix was an example in Apologetics as defined in the heading. Tertullus continues, saying:

"For we have found this man a pestilent fellow, and a mover of sedition among all the Jews throughout the world, and a ringleader of the sect of the Nazarenes: Who also hath gone about to profane the temple: whom we took, and would have judged according to our law. But the chief captain Lysias came upon us, and with great violence took him away out of our hands, Commanding his accusers to come unto thee: by examining of whom thyself mayest take knowledge of all these things, whereof we accuse him. And the Jews also assented, saying that these things were so. Then Paul, after the governor had nodded to him to speak, answered: “Inasmuch as I know that you have been for many years a judge of this nation, I do the more cheerfully answer for myself, “because you may ascertain that it is no more than twelve days since I went up to Jerusalem to worship. “And they neither found me in the temple disputing with anyone nor inciting the crowd, either in the synagogues or in the city. “Nor can they prove the things of which they now accuse me. “But this I confess to you, that according to the Way which they call a sect, so I worship the God of my fathers, believing all things which are written in the Law and in the Prophets. “I have hope in God, which they themselves also accept, that there will be a resurrection of the dead, both of the just and the unjust. “This being so, I myself always strive to have a conscience without offense toward God and men. “Now after many years I came to bring alms and offerings to my nation, “in the midst of which some Jews from Asia found me purified in the temple, neither with a mob nor with tumult. “They ought to have been here before you to object if they had anything against me. “Or else let those who are here themselves say if they found any wrongdoing in me while I stood before the council, “unless it is for this one statement which I cried out, standing among them, ‘Concerning the resurrection of the dead I am being judged by you this day.’ ”(24: 1-21)

Here we see Paul versus Tertullus in a debate setting, the kind of setting we see in trials in court, where the prosecutor and defense attorney debate the law and the facts. Tertullus is a prosecutor representing the high priest and the elders, being hired to prosecute the case, to make the formal accusation. Being an orator for hire, I am sure he was paid well for his rhetorical skills. Paul, unlike the high priest or elders, does not hire someone to speak for him but represents himself. Felix is the judge, being governor and the ruling authority to decide the case. The prosecutor is called upon by Felix to speak first.

He begins with saying "we have found this man a pestilent fellow" and "a mover of sedition" and that "throughout the whole world." He is accused of being a "ringleader" of a cult, of "the sect of the Nazarenes." He also has "profaned the temple." Tertullus is telling Felix that Paul's guilt has already been proven by his accusers and that all that is needed from Felix is merely a formal ratification.

When Paul gives his "answer," his apologia, he denies the charges and accusations. He tells Felix that they have no proof or evidence to back up their accusations. He gives counter evidence to disprove the accusations. Paul says he was not guilty of treason nor an instigator of riots. As far as being a "sect," Paul in essence says - "what my accusers call a 'sect' is the way I worship God, the God of my fathers." In this he appeals to logos, to reason and logic. But, there is also pathos in what he says clearly. Why would it not? His life is at stake in the decision of the court of Felix. Paul no doubt spoke with pathos when he said "I believe everything in the law and prophets." He says "I agree that there will be a resurrection of just and unjust men." He says his conscience is clean and he has no guilt for any of the wrongdoings of which he is accused. He says his having brought alms to the people shows that he has no sinister motives towards his people, and that he was not doing what he does out of greed. Paul also says that the absence of his Jewish accusers at the trial, the absence of eye witnesses, demonstrates the verity of what he is saying. There is ethos, pathos, and logos revealed in the above exchange between Tertullus and Paul.

Paul wrote:

"For when we came into Macedonia, we had no rest, but we were harassed at every turn—conflicts on the outside, fears within. But God, who comforts the downcast, comforted us by the coming of Titus, and not only by his coming but also by the comfort you had given him. He told us about your longing for me, your deep sorrow, your ardent concern for me, so that my joy was greater than ever. Even if I caused you sorrow by my letter, I do not regret it. Though I did regret it—I see that my letter hurt you, but only for a little while— yet now I am happy, not because you were made sorry, but because your sorrow led you to repentance. For you became sorrowful as God intended and so were not harmed in any way by us. Godly sorrow brings repentance that leads to salvation and leaves no regret, but worldly sorrow brings death. See what this godly sorrow has produced in you: what earnestness, what eagerness to clear yourselves, what indignation, what alarm, what longing, what concern, what readiness to see justice done." (II Cor. 7: 5-11 NIV)

Wow! What pathos in these words! Notice all the bold words above. They are words that speak of various moods and emotions, of passion, of feelings, such as "fears within," "deep sorrow," "longing," "ardent concern," "joy," "happy," "regret," "hurt" (feelings), "earnestness," "eagerness," "indignation," "alarm," "readiness," etc. Paul is unlike the Stoics in regard to the emotions. He does not see all emotion and passion as in need of repressing. Many feelings are good and should be paid attention to and properly interpreted. Why do you feel the way you do? That is what Paul would have all to consider. Is it a good feeling? What are the consequences or fruit of the feeling?

Another instance of Paul's pathos in speech can be seen in this case.

"And when the people saw what Paul had done, they lifted up their voices, saying in the speech of Lycaonia, The gods are come down to us in the likeness of men. And they called Barnabas, Jupiter; and Paul, Mercurius, because he was the chief speaker. Then the priest of Jupiter, which was before their city, brought oxen and garlands unto the gates, and would have done sacrifice with the people. Which when the apostles, Barnabas and Paul, heard of, they rent their clothes, and ran in among the people, crying out, And saying, Sirs, why do you these things? We also are men of like passions with you, and preach unto you that you should turn from these vanities unto the living God, which made heaven, and earth, and the sea, and all things that are therein: Who in times past suffered all nations to walk in their own ways. Nevertheless he left not himself without witness, in that he did good, and gave us rain from heaven, and fruitful seasons, filling our hearts with food and gladness. And with these sayings scarce restrained they the people, that they had not done sacrifice unto them." (Acts 14: 11-18)

On this occasion the Pagans thought that Paul and his companion were "gods" come down in human flesh. This was due to the miracle of the healing of a lame man. Notice how Paul and Barnabas react with passion and how they appeal to logos and pathos, to intellect and emotion. Men do not tear their clothes in a Stoic manner! Notice the passion in their rhetorical "Sirs, why do you do these things?" Though there is no exclamation mark in the above, it may well be added. "Why do you do these things?!" Or, in modern speech, we may translate as "what are you doing?!" Next he says "we are men of like passions with you." There we have the word "passions." That word is from the Greek word "homoiopathes" which compound word includes a form of the word "pathos." It is an adjective describing the kind of "men" they were claiming to be. "We are passionate men, just as you are," Paul essentially says.

Who can fail to see the passion in Paul's exhortation when he says that "we preach unto you that you should turn from these vanities"? He surely does not mean that he stoically exhorted them. He certainly did it with both logos and pathos. Elsewhere Paul wrote:

"By the humility and gentleness of Christ, I appeal to you—I, Paul, who am “timid” when face to face with you, but “bold” toward you when away!" (II Cor. 10: 1 NIV)

Who can fail to see the pathos in Paul's "appeal" making? He did not simply appeal to men's minds, to their intellect and reason, but to their feelings. So should we.

No comments:

Post a Comment