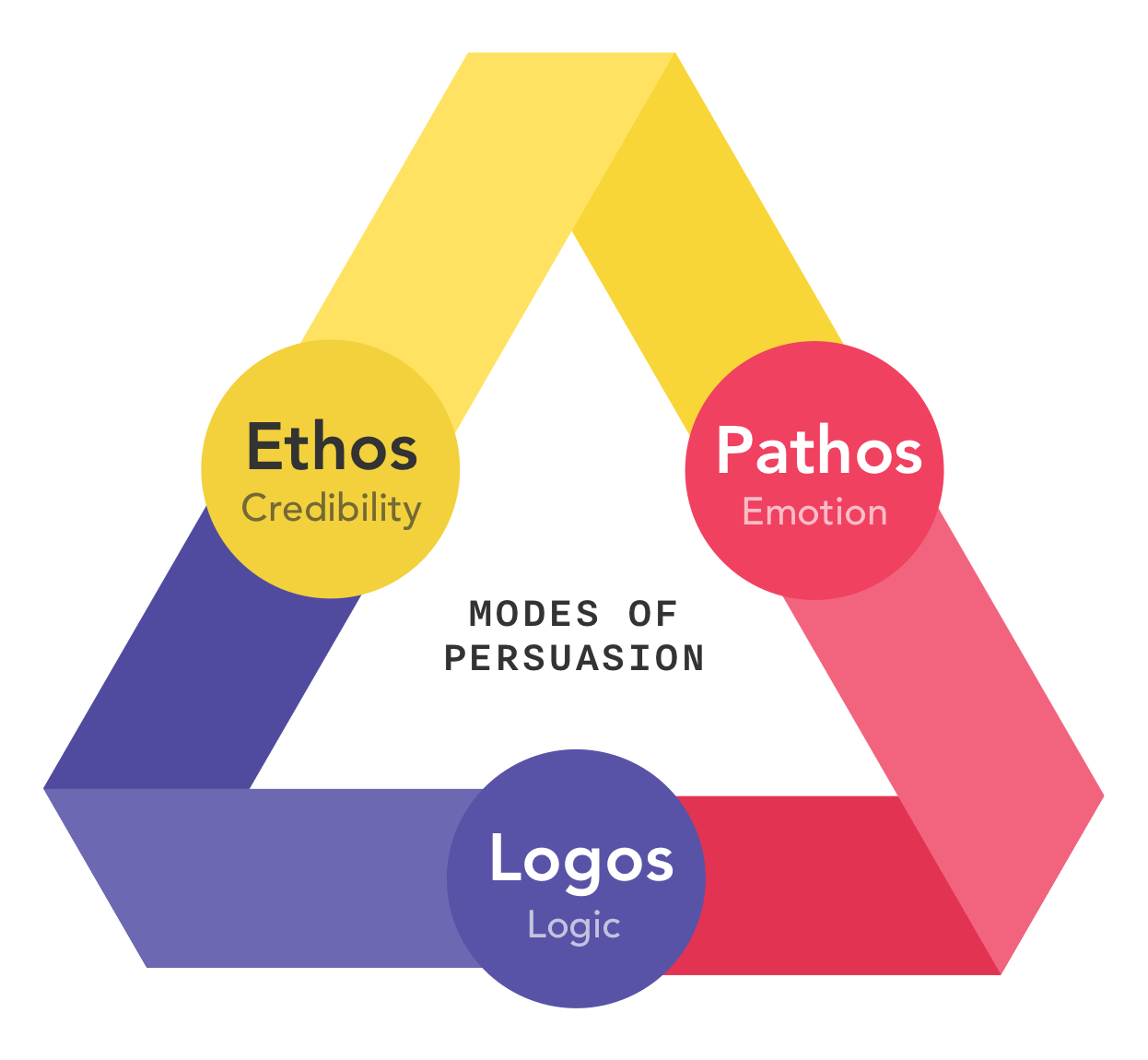

Ethos, Pathos, & Logos

Ethos is about establishing your authority to speak on the subject, logos is your logical argument for your point and pathos is your effort to sway an audience emotionally.

Ethos has to do with the speaker, with his credibility, authority, and character. It involves a speaker's credentials, the reasons why he should be heard or "worth listening to." It also includes dressing appropriately, using a good choice of words, giving the impression that the speaker is sincere and honest by his demeanor, deportment, and the way things are spoken or characterized.

Pathos has to do with the hearers of a speaker and with their emotions, including their prejudices and biases, as we see in "emotional appeals," or when a speaker seeks to "draw pity from an audience," or when he seeks to excite and arouse sentiment. Speakers want people to "experience" and feel the weight and intensity of the discourse, to receive it with the same passion in which it is spoken, to feel a certain way.

Logos is an appeal to logic and reason, to concrete fact and proof, to authority. Words, speech, or argument first reside in the mind of the speaker before it is communicated to the audience. Thus, just as pathos appealed to emotion so logos appeals to intellect.

The Sophist tradition in Corinth and in the Greek world was strong in the minds of the first Christian converts in Corinth. We have already spoken much of this and of the fact that Paul addresses various Greek philosophies in his letters to the Corinthians.

Paul called himself the "apostle to the Gentiles" (Rom. 11: 13) and said that he was especially sent to preach the glad tidings to "Greeks," though he did as well to the Jews. He knew Greek philosophy. He knew the Greek mind, its worldview, its values, beliefs, traditions, etc. He knew about Aristotle's "means of persuasion" and of the philosophical talk about rhetoric and debate. He knew all this and was therefore a fit "ambassador" for Christ and his kingdom in relation to the world. To the Corinthians Paul said that he and other evangelists were "ambassadors for Christ, as though God did beseech you by us." (II Cor. 5: 20)

It is required that an ambassador know his own people, his own country, its laws, customs, values, beliefs, etc. He represents his country, acting by its authority, by appointment of its king, governor, or president. It is required that an ambassador know much about the country to which he is appointed to deal with or else he would be of little value. So Paul knew much about the Greeks and Gentiles, about their beliefs, culture, laws, customs, etc. It can well be argued that Paul was chosen by the Lord to be his special ambassador to the Gentiles because he had previously and providentially been trained in Gentile and Greek literature.

The Sophists were orators, public speakers, mouths for hire in an oral culture. They were itinerant tutors who claimed to teach all that was necessary for "success in public life," how to "get ahead." They mainly taught rhetoric and related fields such as grammar, history, and literary criticism, psychology, etc., but all for the wrong reasons and ends. They were also in many cases the lawyers of the day, paid advocates, people who could argue either side of a case.

When cases are tried by public opinion, those who can best sway, via rhetoric and debate skills, the assembly of citizens assembled to try cases, are most desired by defendants, those who have been accused. This was the case with Paul when he stood on the mount in Athens when on public trial for his discourse, for his "logos." (Acts 17) There he gave his "apology," that is, his "rational verbal defense." In this he had to "answer" the charges of his accusers. (I Peter 3: 15, discussed previously)

"Now while Paul waited for them at Athens, his spirit was stirred in him, when he saw the city wholly given to idolatry. Therefore disputed he in the synagogue with the Jews, and with the devout persons (Greeks), and in the market daily with them that met with him. Then certain philosophers of the Epicureans, and of the Stoicks, encountered him. And some said, What will this babbler say? other some, He seems to be a setter forth of strange gods: because he preached unto them Jesus, and the resurrection. And they took him, and brought him unto Areopagus, saying, May we know what this new doctrine, whereof you speak, is? For you bring certain strange things to our ears: we would know therefore what these things mean...Then Paul stood in the midst of Mars' hill, and said, Ye men of Athens, I perceive that in all things ye are too superstitious." (Acts 17: 16-20, 22)

The learned elite, who were Paul's accusers in Athens, were skilled Sophists. They knew every trick in the book when it comes to winning an argument. In the above encounter with the philosophers their Sophistry is clearly on display. They first make ad hominem attacks, calling Paul a "babbler." They attack his ethos, his credentials and character, and also summarily dismiss his logos without a reply in kind, they appealing to pathos, to the emotions and biases of the people.

They accused him of preaching a "new doctrine," of "setting forth strange gods (Greek demons)" of reporting "certain strange things," weird theology. They accuse him of innovation in religious belief, of teaching absurd ideas, as in affirming that the Son of God and savior of the world died on a cross, and that he was physically resurrected after being dead three days.

They make use of "insinuation" as a tactic, insinuating things about Paul that would lead people to think that he was not worth their time listening to. They "cast aspersions," using an old ad hominen tactic called "poisoning the well." By their preemptive and unfounded aspersions, insinuations, and denunciations, they intended to create doubt and suspicion in the minds of the audience about Paul's credibility, his character.

The people were curious to hear Paul for of the Athenian people it is said (vs. 21) that they spent their time in hearing or relating "news," about new ideas, new events, new public celebrities, etc. The philosophers, as well as some of the Jews and Pagans ("devout persons"), were not as curious as they were fearful and angry. They were afraid of losing followers, money and prestige, and were angry that some "upstart" from the poorer class could "outdo" them in logos, could attract attention. But, sometimes this tactic can "backfire," for when a speaker is "talked down" much by his opponents it can spur the curiosity of people to hear such a person even further. It can also backfire further if the speaker turns out to be much better than how he was depicted by his opponents.

The learned philosophers of the several schools mentioned only joined into a discussion with Paul because they saw many people listening to what he was saying and they were both jealous and afraid for their own standing. Had no one paid any attention to Paul, then they would also have paid no attention.

The verbal defense that Paul gave on Mars Hill, in the Areopagus, was an excellent discourse. It has none of the flattery of the Sophists, no "eulogies" for the citizens, no boasting of credentials, no foolish questions. Rather he begins by saying that "they are too (overly) superstitious (or religious)." (vs. 22) He gets right to the issue. He is bold and frank. At the end of his defense the record says:

"And when they heard of the resurrection of the dead, some mocked: and others said, We will hear thee again of this matter. So Paul departed from among them. Howbeit certain men clave unto him, and believed: among the which was Dionysius the Areopagite, and a woman named Damaris, and others with them." (32-34)

Notice the different reactions to Paul's discourse (logos). Notice how the "disputers of this age" are left speechless, saying "we will hear from you again on this matter." They obviously needed time to figure out a way to deal with Paul, either in argumentation or through violence. There was also an implied threat in their remarks. They were informing Paul that he would be "called on the carpet" for what he has said. Among the lay people some did not believe and resorted to mocking and ridicule and yet a few, God's elect, "believed."

The Sophists "paid for hire" speakers spawned the word "sophism" as a result of their "artful dodger" type of argumentation. "Sophism" is "a plausible but fallacious argument, or deceptive argumentation in general. In rhetorical studies, sophism refers to the argumentative strategies practiced and taught by the Sophists." (See here) Sophism is what Paul saw in his opponents in Athens and he saw it on many other occasions.

From Athens Paul goes to Corinth where he will encounter again the same Sophists.

"After these things Paul departed from Athens, and came to Corinth...And he reasoned (dialegomai) in the synagogue every sabbath, and persuaded (peithō) the Jews and the Greeks." (Acts 18: 1,4)

The word "dialegomai" means to "converse, discourse with one, argue, discuss." The word "peitho" means to persuade, to convince, to get someone to agree, or to give credit to a discourse. It is not only the duty of apostles to "reason" and debate, to persuade by convincing argument, but also every believer to one degree or another, as we have previously shown. This also was a habit with the apostle who invited debate and open discussion of what he preached. Notice these other instances of Paul's apologetic speech.

"And he went into the synagogue, and spake boldly for the space of three months, disputing and persuading the things concerning the kingdom of God." (Acts 19: 8)

"Moreover ye see and hear, that not alone at Ephesus, but almost throughout all Asia, this Paul hath persuaded and turned away much people, saying that they be no gods, which are made with hands" (Acts 19: 26)

Again Paul disputed, reasoned, persuaded, and spoke plainly and boldly and yet the Sophists judged it as a "turning away" of people from truth, even though "much people" were listening to him and some agreeing with him. Paul was seeking rather to "turn away" the people from Paganism and false religion and to the pure religion of Christ.

Paul's Ethos

"And I, brethren, when I came to you, came not with excellency of speech (logos) or of wisdom, declaring unto you the testimony of God. For I determined not to know any thing among you, save Jesus Christ, and him crucified. And I was with you in weakness, and in fear, and in much trembling. And my speech and my preaching was not with enticing words of man's wisdom, but in demonstration of the Spirit and of power: That your faith should not stand in the wisdom of men, but in the power of God." (I Cor. 2: 1-5)

Paul came not with excellency or superiority of speech? But, is not Christian speech more elevated than the speech of unbelievers, even of the world's elite speakers and persuaders? Have we not seen how believers, especially apostles, are superior in their logos, in their speech and conversation? Did not Paul have excellent logos on Mars Hill? Surely Paul means that he did not come with superior speech by the judgment of the Sophists, by the opinion of the teachers of rhetoric and persuasion skills in the elite schools, by the judgment of the world. To the believer the discourses of the apostle are most excellent! So he said in those keynote words of his opening words to the Corinthian believers: "the logos of the cross is to them who are perishing foolishness but unto us who are being saved it is the power of God." (1: 18)

If one defines "excellent speech" as that which uses lots of flattery and "fancy talk," or "flowery language," then yes, Paul was not excellent, but inferior. But, the standards for judging profitable talk are different for the believer than they are for the unbelieving Sophist. God defines "excellent speech" one way and the world defines it in a different way. Certainly Paul's logos was far superior as concerns the substance of his words. The only way it could possibly be inferior was in style and rhetoric, and, by Sophist standards, his speech was not excellent, not eloquent. But, by a higher standard, Paul's rhetorical abilities excelled that of the Sophist smooth talkers.

Paul says that his "speech and preaching was not with enticing words of man's wisdom." So, if use of "enticing words" be one of the things that determines "excellency of speech," then Paul's speech was anything but excellent, was not superior to the Sophist and their professional talk. Many translations use the word "persuasive" instead of "enticing." Paul is not condemning being persuasive in speaking, for he himself was very persuasive. But he is condemning a kind of persuasion exercised by the Sophists. In fact he identifies the kind of persuasive words he intends when he adds "of man's wisdom." The "persuasive words of God's wisdom" (implied) is set in opposition to "the persuasive words of man's wisdom."

The Sophists were taught about what Aristotle called "all the available means of persuasion." The Sophists came up with all kinds of ways to persuade, ways that were not always principled and right, as we have already spoken. It is the same kind of persuasion we see in advertising done by marketers. Sophist like marketers are able to "talk people into" believing what is said about a product and into buying it.

Paul's Parousia

Paul says that his physical presence and demeanor was not up to the standards of the Sophists. There was nothing "sophisticated" about his person, his bodily appearance, his clothes, nor of his "coming," which did not include, as it did with the popular Sophist speakers, a trumpeted arrival, a pompous entrance into an auditorium or amphitheater, and much "stagecraft."

In any college speech class one is taught the importance of bodily deportment and of the proper use of the body's physical members in giving speeches or talks. You are taught how to stand, how to look at the audience, how to use or not use your hands, etc. You are taught the importance of "first impressions," how it is important to dress appropriately for the type of discourse being given, and for the setting and type of audience. Dress, grooming, erect stature, strong voice, pleasing face, healthy look, bold spirit, etc., are taught in speech communication. The speaker's bodily appearance includes demeanor and deportment. All this is part of the speaker's ethos, what the audience sees in the speaker or knows by report or reputation.

Paul tells the Corinthian believers that when he visited Corinth and spoke to them that he was with them "in weakness and fear and much trembling." Later in second Corinthians Paul cites the opinion of the Sophist rhetoricians regarding his bodily appearance:

"For his letters, say they, are weighty and powerful; but his bodily presence is weak, and his speech contemptible." (II Cor. 10: 10)

By elitist standards, this would be a sizable demerit as respects Paul's credentials as a reputable speaker. Yet, ironically, his speaking was "in demonstration" of both the Spirit and "of power." Powerful speech from such a man of "weak presence"! But, this is a fitting example of God's choosing and using "the weak things of the world to confound the things which are powerful." (I Cor. 1: 27) In Paul's second epistle to Corinth he cited the words of his Sophist critics. In the words "his bodily presence is weak" the criticism is that Paul's "presence" is unimpressive. The Greek word for "presence" is "parousia." Let us first define "parousia" and see how it relates to a speaker's ethos.

In the above passage "parousia" is translated into English by the word "presence" and for the above passage this is a good translation. Notice also these words of Paul:

"Wherefore, my beloved, as ye have always obeyed, not as in my presence (parousia) only, but now much more in my absence (apousia), work out your own salvation with fear and trembling." (Phil. 2: 12)

Parousia denotes presence while apousia (literally "without presence" or "not present") denotes absence. More often however the word is translated as "coming." Notice these instances:

"the coming of Titus" (II Cor. 7: 6)

"the coming of Stephanos" and et als (I Cor. 16: 17)

"the coming" of the "man of sin" (II Thess. 2: 9)

"my coming to you again" (Phil. 1: 26)

Parousia is also one of the words often used in the new testament for the second coming of Christ. It also is never used in reference to his first coming. There is an interesting reason for this as we will see. On the meaning of parousia Vine's NT Words says:

"Lit., "a presence," para, "with," and ousia, "being" (from eimi, "to be"), denotes both an "arrival" and a consequent "presence with." For instance, in a papyrus letter a lady speaks of the necessity of her parousia in a place in order to attend to matters relating to her property there. Paul speaks of his parousia in Philippi, Phl 2:12 (in contrast to his apousia, "his absence."

Notice how the use of the word may sometimes focus on arrival or advent rather than on the continuous presence following. When the focus is on the former it is better to translate as "advent," "arrival" or "coming." When the focus is on the latter it is better to translate as "presence." In each instance it involves the appearing of a person in his physical body. It never denotes a spiritual coming or mental coming. Yet, Paul did speak of his spirit being present when his body was absent.

"For I verily, as absent in body, but present in spirit, have judged already, as though I were present, concerning him that hath so done this deed." (I Cor. 5: 3)

By Paul's being present in spirit in Corinth when absent (Greek "apeimi" denoting absence or departure) in body he no doubt refers to his words remaining with the believers when he was gone from them. It involves their memory of both his words and his spirit. But, Paul does not use "parousia" (nor "apousia" for absence) for "present" it being from the Greek word "pareimi" which is another word for presence.

Paul does not use the word "parousia" when he says he "came" to Corinth but the Greek word "erchomai." Paul's critics, as we have seen, referred to Paul's "bodily presence (parousia)," when they described it as being "weak." Paul does use parousia in other epistles in regard to his coming, and to the comings of other ministers, but more often he uses "erchomai." The same is true in regard to the second bodily coming of the Lord Jesus Christ. Both words are used to refer to it although there is a distinction to be observed in the several contexts in which they are used. Parousia occurs only twenty four time in the New Testament while erchomai occurs about six hundred times. Erchomai is a more general term for the coming of a person to another person or to a place. As we will see, however, parousia is used mostly as a technical term for the visit of a king or prince, for a "royal visit," as well as for other celebrities and dignitaries, including popular speakers. As such it includes all the appurtenances of such visits.

Formal Receptions

When a head of state visits another head of state there are what are called "state visits" and as such include much pomp and circumstance. Wrote one commentary:

"The BDAG Greek-English lexicon says that parousia was “the official term for a visit of a person of high rank, esp. of kings and emperors visiting a province.” Robert Mounce writes that parousia “is widely used in non biblical texts for the arrival of a person of high status” (New International Biblical Commentary). Ann Nyland writes that the Emperor Nero wanted as many people present as possible at his parousia to Corinth (The Source New Testament; note for Matt. 24:3). Visits by dignitaries were expensive, so the cost of the “visit” was often paid for by special taxes that were levied, making the parousia of a high-ranking official a burdensome event for many people. A parousia was a public event, because kings and dignitaries arrived with great pomp and pageantry." (See here)

Important and popular speakers when visiting a city also did much to promote their parousia. The same is true in our day. When politicians visit cities in campaigns and have rallies, they too have much cost involved in organizing and preparing for the visit, a cost often paid by supporters and contributors. There is much planning involved in the stagecraft, in the gala and pageantry, in the pomp and circumstance. Knowing this about the meaning of "parousia" we can better see what is intended in the criticism of Paul by the Sophists in Corinth when they said "his bodily parousia is weak" (or powerless). By this they mean that Paul lacked the normal dignified and enthusiastic advent that comes to the popular speakers and lecturers. And, Paul never denied this criticism. What Paul attacked was the fallacious premise of the Sophists which affirmed (in their criticism) that no good or truthful speaker could possibly lack such an advent.

Paul's informal and lackluster parousia to cities in preaching the gospel was designed by God to demonstrate something to all who would hear the apostle (and other apostles and evangelists too). The Lord was showing what Paul said in his opening words to the Corinthians (which we have previously examined).

"For you see your calling, brethren, how that not many wise men after the flesh, not many mighty, not many noble, are called: But God has chosen the foolish things of the world to confound the wise; and God has chosen the weak things of the world to confound the things which are mighty; And base things of the world, and things which are despised, has God chosen, yea, and things which are not, to bring to nothing things that are: That no flesh should glory in his presence." (1: 26-29)

Paul, as regards his physical form and appearance, had no symbols of high status, no expensive clothes and jewelry, no makeup and perfume, etc. He was "weak" and "base" and "despised," a "thing of nothing," in respect to such things, but God was showing men that truth and logos and power come from him and not from men. In this way neither Paul nor his teachers could take credit for the power of the "logos of the cross" preaching. People could see that the power of gospel speaking was not a result of Sophistic training.

In an article titled "Did Paul have a body image problem" Nathan Campbell says (here):

"Bruce argues in The Entries and Ethics of Orators and Paul (1 Thessalonians 2:1-12) that Paul was perhaps worried that the Thessalonians were drawing parallels between himself and the famous orators, or sophists, of his day, a position he argues that he consciously did not choose in Corinth because the Corinthians were rhetorical fanboys who wanted the apostles to be like the famous orators so that they could copy them and join the club, not like little old Paul who instead of coming to town like a flashy orator knowing everything and delivering extemporary speeches by request, came to town “knowing nothing but Christ crucified.”

So very well said. Keep in mind that Paul's parousia is part of his "ethos" as a speaker. Sophists judged his credibility as a speaker and teacher in part by his lack of sophistic advent. Paul purposed not to follow the Sophists in this. To "come" in such fashion would detract from his message rather than enhance it. Also, his plain talk shows again how he will not follow the Sophists in their persuasive tactics. "Orators were a pretty corrupt bunch, in it for fame, fortune, and praise," says Campbell. He also said:

"Paul’s measure of success runs counter to that of his sophist contemporaries, he’s not interested in crowds or fame or fortune – but rather in lives turned to God. Paul provides an account of his methods contrary to the methods of the sophists: For the appeal we make does not spring from error or impure motives, nor are we trying to trick you. On the contrary, we speak as those approved by God to be entrusted with the gospel. We are not trying to please people but God, who tests our hearts. You know we never used flattery, nor did we put on a mask to cover up greed—God is our witness. We were not looking for praise from people, not from you or anyone else, even though as apostles of Christ we could have asserted our authority. Instead, we were like young children among you."

Again, he hits the mark on Paul's idea about "sound speech" and good discourse and how it runs counter to that of the Sophists. He says further:

"Paul’s approach, as described here, could hardly be confused with that of the sophist. And it seems he deliberately intended to present his parousia as anti-sophistic."

"Secondly, he further reflects on the relationship of rhetoric to his presentation. ‘And I was with you in weakness and fear and much trembling’—hardly the υπόκρισις recommended by Philodemus in his lengthy discussion in his treatise on the rhetoric of ‘bodily presence’ with gestures and voice. Further, his ‘rhetoric’ and preaching were not undertaken with persuasive rhetorical techniques. On the contrary, his message (λόγος) and preaching (κήρυγμα) were not in the persuasiveness of wisdom. He did not engage in the ‘demonstration’ (αποδείξις) of ‘proofs’ (κήρυγμα) used by the orators in the ‘art of persuasion’ but by that of the Spirit and of power. The purpose of so doing was spelt out by Paul—so that the Christian’s ‘faith’ or ‘proof’ (πίστις) would not rest in the wisdom of men i.e. the orators but in the power of God.”"

Again, this is well stated and Paul's letter to the Corinthians has much to say about good speech as scripture defines it versus how the Sophists define it. Campbell says further:

"Bruce’s conclusion:

Paul as a preacher had reflected not only on the use of classical rhetoric for the presentation of his message and rejected it. He also resolved in his own mind that it was highly inappropriate for the messenger of the gospel to adopt the εἰσοδος conventions and ethics which governed the first century orators and sophists on their initial visit to a city and their long term relationships with its citizens."

How unlike is Paul to the world's greatest and most popular speakers!

Sophists would charge in advance for seats in the auditoriums. Paul did not. Sophists would begin their discourses by flattering the audience and the city, followed by bragging about their credentials. Paul did not. The power of Paul's logos was not in his rhetorical skills, or in the sound of his voice, but in the substance of what he was reporting. He had news concerning the salvation of the world. He had "news" of a crucified and risen Savior. The power is in the news itself and in the influence of the Spirit of God.

In the next post we will continue along these lines and discuss Paul's pathos.

No comments:

Post a Comment